Amber Ratto, a paramedic, was a few miles from the Las Vegas Strip when her ambulance got the call on Sunday night: active shooter, at least 20 people shot.

“I got goosebumps all over. My heart just sank because I knew this was real, that people had been hurt.”

Minutes later Ratto, 26, stepped into the scene of the most murderous mass shooting in modern United States history: an outdoor country music festival with dozens of dead and dying, hundreds wounded and thousands fleeing for their lives.

Amid the chaos Ratto and her colleague, who work for American Medical Response (AMR), a private ambulance company, loaded a husband and wife into the back. The woman had been shot in the head but the husband, shot in the stomach, was in graver condition.

“They were in their 50s. He had blood all over him and was holding a dressing to his abdomen. I taped it really, really hard and started multiple IVs to try to keep him alive. His wife was was calling their daughter saying they had been shot but that it would be OK. In my head I was thinking, I sure hope so, because I don’t know. His body was completely pale and he was going into shock.”

It was the start of a long, terrible night for Las Vegas’s first responders and hospitals – 59 dead, more than 520 wounded and uncertainty over further attacks.

Grisly scenes awaited Ratto at Sunrise Hospital & Medical Center, which resembled a war zone. “Blood just soaking the hallways, everywhere. My guy had to go straight into ER because he was bleeding out internally.”

Ratto, covered in blood, and her colleague drove back to the concert site, braced for gunfire. “I turned off the lights in the back of the ambulance to not be targets.” Ratto treated people at the concert site and covered the dead. “We had sheets on them. There were so many dead.” Ratto spoke in an interview on Tuesday, still uncertain whether “her guy” survived.

The killer did not. Stephen Paddock took his own life after raining down havoc with a high-powered arsenal from the 32nd story of the Mandalay Bay hotel.

Hospitals were left to deal with the consequences.

Robert Smith, a cardiovascular technician at the University Medical Center of Southern Nevada, could tell it was bad even before he reached the emergency room.

“Blood on the ground in the car park – trails of blood about 20ft from the entrance. That’s where they were dropping off the people.”

Some walked and staggered, moaning and wailing, others lay on stretchers, motionless and silent, all with gunshot wounds or injuries sustained in the scramble to escape.

Some had multiple wounds to the the head, face, chest, body, arms and hand, others had just a single wound or abrasions, testament to the indiscriminate fire.

“You couldn’t think about your own world, your own problems. You had to focus on the patients to save as many lives as possible,” said Smith, 59, speaking on Tuesday during a brief break at the hospital which ended when his pager beeped.

The rampage killed 59 people and wounded more than 520. The University Medical Center of Southern Nevada, known as UMC, received about a fifth of the wounded.

It is the only level-one trauma center in Nevada and one of the US’s only free-standing trauma units, an integrated facility permanently staffed with surgeons and trauma nurses, with 11 trauma bays, three operating rooms, a CT scanner and a trauma intensive care unit.

Staff train to handle disasters and mass casualties. Even so, the scale and intensity of the influx on Sunday and Monday stretched them to the limit. Beds, gurneys and wheelchairs swiftly filled, staff had to raid other departments for additional IV tubing, blood pressure cuffs and blankets, and still patients kept coming.

“The main challenge was to stay calm and to think straight,” said Pat Archer, a lab technician who processed blood samples.

‘Very clear this was a high-powered weapon’

“I have no idea who I operated on,” Jay Coates, a trauma surgeon, told AP. “They were coming in so fast, we were taking care of bodies. We were just trying to keep people from dying. Every bed was full. We had people in the hallways, people outside and more people coming in.”

Huge, horrifying wounds on his operating table told him this shooting was different. “It was very clear that the first patient I took back and operated on that this was a high-powered weapon. This wasn’t a normal street weapon. This was something that did a lot of damage when it entered the body cavity.”

Off-duty staff members rushed to the hospital to help. A student nurse who gave her name only as Joanne said she was turned away. “They said I’d be in the way. They were so busy, so focused.”

A key challenge was prioritising the wounded – the loudest and bloodiest are not necessarily the gravest cases. A scale of one to five rates one as the most critical.

Those deemed to have unsurvivable injuries were reportedly placed in a separate area to receive comfort care until they died, a standard practice.

A group of four clinical technicians on a smoking break outside the main entrance disputed that account. “They say that all those who made it here alive are still alive,” said one, prompting nods from her colleagues. “All of them,” said one.

UMC’s official spokesperson was unavailable for comment.

With staff working marathon hours ordinary residents flocked to UMC to offer cookies and other treats, said Smith, the cardiovascular technician. “No one wanted to eat so there were lines of people coming down the hall looking to help, to give us stuff. My daughter brought water, blankets and donuts.”

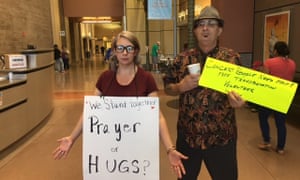

On Tuesday volunteers manned the reception area offering lifts, toys, treats and comfort. Ashley Schuck, 28, wore a placard: “We stand together. Prayer or hugs?” People were opting for both, she said. “This community is blowing it away. This is not Sin City.”

Ratto, the paramedic, said she was still processing the horror but felt proud. “So many died but we saved so many. I feel lucky. I have the best co-workers in the entire world.”

Facebook

Facebook

No comments:

Post a Comment